Welcome to the

Run on Sun Monthly Newsletter

In this Issue: |

July, 2013

Volume: 4 Issue: 7

Intersolar 2013 - Hot, Not and IdioticIntersolar North America 2013 (IS for short) was in San Francisco this month and we were there - here is our first take on who was Hot and who was oh, so, Not at the show (and Recom, we mean you). Heat CheckAny time you come to a tradeshow - whether it is IS or SPI - part of the task in reporting back is to get a gestalt for the show as a whole. One sense of that comes from raw numbers - according to Intersolar, the number of exhibitors dropped from 757 in 2012 to 577 at this event, a decline of 23.7%. And certainly there were some major players missing in action such as module makers LG Electronics and SunPower, and microinverter king, Enphase Energy. (We understand that it has always been their strategy to pass on IS as "too local" in favor of SPI - but the rumor is that they will be passing on a booth at SPI this year as well!) Of course, Enphase proved that it is possible to make a splash at a show without a booth (see below) but we wonder if this is the start of a trend toward major downsizing of these events? Aside from the numbers, here was our gut-check on the expansiveness of the show - where were all the bags? In years past it seemed that every major booth was giving out branded shopping bags that attendees could use to gather info from all of the other booths (and to carry home groceries thereafter!). This year - no bags, other than the clumsy paper version provided by IS when you registered. Without a proper bag we kept our acquisitions to a minimum - I kept one handout, from storage system manufacturer Stem (more on that in a later post) and lots of business cards. Meaning my flight home was the lightest ever. Making a SplashIn many ways, Enphase Energy was the star of this show. Not only did they utilize the posh, Four Seasons Hotel to roll out their 4th Generation microinverter product along with some very cool upgrades to their Enlighten data visualization service (about which we will devote an entire post later in the week) but they also played host to two of the major events at IS - all the while not staffing a booth on the exhibit floor. The IS Tweetup - hosted by Tor Valenza (aka SolarFred) and co-sponsored by Enphase and Solar Power World - was a huge hit. The room was packed and we were able to see lots of old friends, connect with some new ones whom we had only known via social media previously, and have a very tasty meal. [Shoutouts to Nick Carter (who runs a cool site devoted to our favorite synthesis of EV & PV), Jon Semingson (of MRI Network) and Adam Gerza (who has the awesome gig of being a solar guy charged with directing governmental affairs for Sullivan Solar Power).] Then Tuesday evening, Enphase was one of the hosts at the annual Summer Solarfest party. Again, this is one of those events where lots of networking takes place and people exchange catch-up information - like who has gone where and other fun rumors. We were able to talk with a number of Enphase folks during both of these events and it really helped to have a greater understanding of the company's strategy going forward. And then, just like that, they were gone! We suspect more companies are going to adopt this approach - eschew the booth in favor of more closely targeted events where you can connect with the people you most want to during the show opportunity. While there is certainly more bang for the buck from that approach - and no doubt that matters a lot to a recently gone public company still trying to reach profitability - but there is the downside of not making that serendipitous connection. Given that we got hooked on Enphase by just such an occurrence at a small data monitoring conference years ago, we would hate to see those opportunities slip away. Rock OnWhile the exhibit floor was definitely not as Hot as in years gone by, there was another floor that was as Hot as ever - and that was the one found at the annual Solar Battle of the Bands. Thanks to a miracle ducat from the folks at Quick Mount PV - shoutout to Ron Jones - we were able to attend this year's sold-out event. The action ranged from way cool blues... ...to the hottest of the hot! The crowd loved it! Great to see industry folks hang out a bit and enjoy the many talented people in this biz. How Cool is This?As you walk the floor a common question that colleagues ask each other is - what is the coolest thing you have seen? When a show covers so much floor space - module makers on the first floor, inverters on the second and racking/BoS folks on the third - it is easy to overlook something. Well we found what was the coolest thing at the show, hands down - the folks from QBotix - Solar Powered by Robotics.

The QBotix solution is to get rid of the motors and electronics on the trackers themselves - leaving only a series of sealed gears connected to flanges on the base. Now introduce a robot - that yellow device on the rail in our picture - and program it to follow that rail from tracker to tracker throughout the array. When it arrives at one it stops, engages the gear box flanges and spins them, repositioning the array for that time slice. Then on it goes to the next, repeating that process, until every tracker in the array has been adjusted. It then parks itself (where it recharges!) and then repeats the process so that the array is re-aligned every 45 minutes. Now how cool is that? So far the company only has a couple of relatively small test installations. But their booth was the hit of the show, always with lots of folks standing in awe at the creativity behind this concept. We don't know if this will ultimately prove to be a viable solution to the dual axis tracking problem, but we certainly do salute their innovative approach. We will keep an eye on these folks going forward. Nicely done!

Cages? Really, Cages?Besides trying to track down what is cool, the other question that folks ask while wandering the floor is what is the worst thing you have seen. Alas, that is a question worth asking given the pattern of seeing tacky, outright sexist displays that are passed off as marketing. That pattern plunged to new depths this year when the geniuses at Recom - a module manufacturer headquartered in Greece - came up with the brilliant idea of putting women in cages to advertise their products. Seriously.

So what is the connection between solar modules and women wearing torn clothing, confined in cages? Besides none, of course? Apparently Recom's modules are named after a Leopard and a Panther so the obvious marketing choice is to highlight those products by exploiting women in cages. Obvious, that is, if you are a sexist idiot with the maturity of a high school sophomore boy - with apologies to sophomore boys everywhere. Lest you think this was just a momentary lapse in judgment, there is this from their website (which no, I'm not linking to):

Seriously. Who are these guys? Well, thanks to LinkedIn we were actually able to track down their Managing Director, Hamlet Tunyan. You can email him at: ht@recom.gr and let him know what you think of his sexism pretending to be marketing. I hope his mailbox melts down. That's it for this slice of IS - here are links to the other two pieces on the show: Poseurs and the Player in the Solar Storage Debate and How Enphase Stole the Show. |

“In many ways, Enphase Energy was the star of this show…”

Help Us Spread the News!

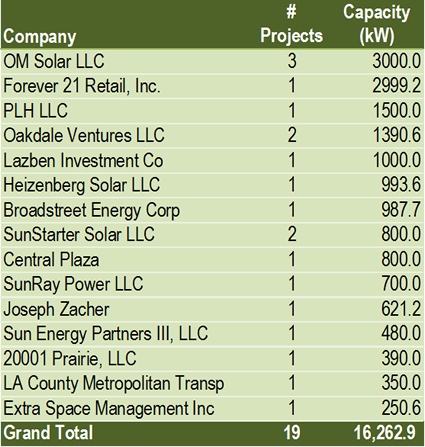

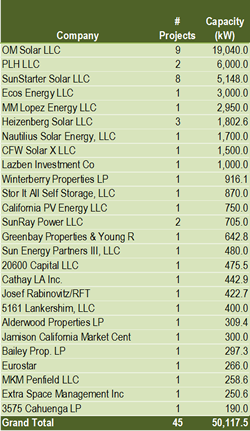

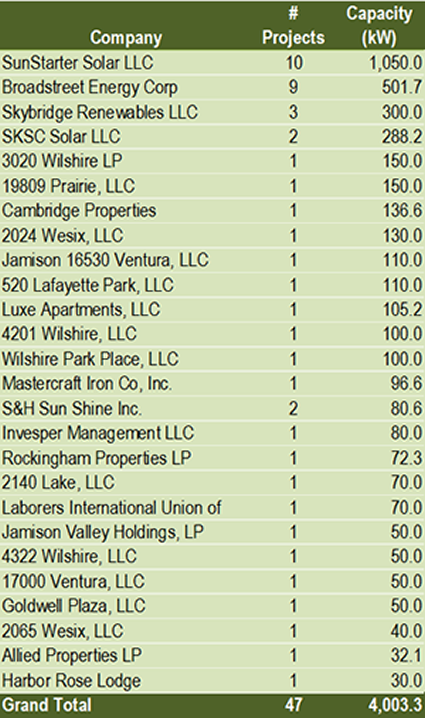

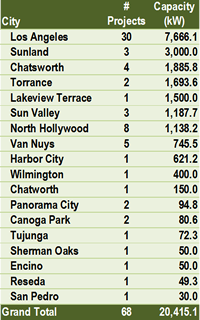

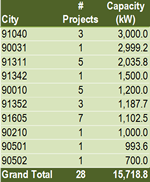

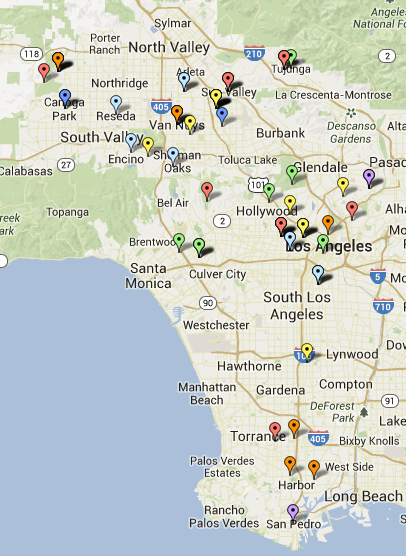

LADWP FiT 2nd Tranche ReportWe have reviewed the data coming from LADWP for the results of the second tranche lottery - here is our analysis. Initial ObservationsOur first observation is that for some inexplicable reason, LADWP chose to present the data in Adobe PDF format instead of the Excel spreadsheets used previously. This made the process of analyzing the data far more tedious than it should have been. Heads up, DWP, please provide data in a data format. We have nothing against PDF files but that is not the way to publish this type of data. Second, there was no Owens Valley data here. We cannot tell if there were no projects submitted from Owens Valley (there were in the first tranche) but none of these projects come from outside the Los Angeles Basin. Third, one of these proposed projects was for biogas and not solar! That proposed project, submitted by MM Lopez Energy LLC, was for a 2.95 MW biogas system in Lake View Terrace. Unfortunately, the tranche was already oversubscribed by 572 kW by the time their lottery number turned up. This is a first for the FiT (which theoretically is technology neutral) - all of the proposed projects in the first tranche were for solar. Collectively, the data released documents a total of 112 proposed solar projects, 63 in the large category (>150 kW) and 49 in the small category (30-150 kW). Large Project Winners & LosersWhile there were a total of 64 projects in the large category, it only took 19 to fully subscribe the 16 MW capacity cap available to large projects, and the last project to make the cut will have to downsize by 263 kW (from its proposed 800 kW) to stay within the cap. Far more numerous, however, were the losing proposals - here they are: Small Project Winners & LosersThere were fewer participants in the small category, with a total of 49 projects of which 47 came within the 4 MW capacity cutoff (although the last project to make the cut will have to trim down by 3.3 kW from its proposed 38.7 kW). Average system size for a successful small project was right in the middle of the allowed range at 85 kW. The two projects that missed the cut were for 41 and 108 kW. Here are the winners: Coming to a Zip Code Near You?As before, the successful projects are scattered about the Basin. On the left is a listing by city, and on the right is the breakdown by top ten zip codes.

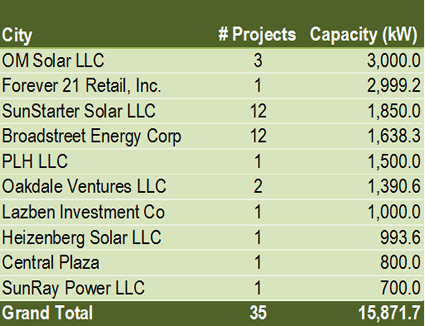

Who Are These Guys?As with the first tranche, there are a great many specially created entities in the list of company names which makes it harder to know who is actually scheduled to do the work. For example, there are numerous proposed projects from companies with names like 17000 Ventura, LLC or Luxe Apartments, LLC - not a lot of insight provided there. Frankly, since the LADWP FiT requirements call for the experience of the installation team as a basis for possible rejection, the published data should identify the installer and not just the project developer. Here are the top ten companies by capacity of winning proposals:

Oakdale Ventures LLC is listed as a foreign (i.e., out-of-state) entity with offices in Chatsworth. Lazben Investments is headquartered in Van Nuys. Heizenberg Solar LLC filed as a business in California on June 7 and appears to be a Delaware corporation headquartered in Denver. SunRay Power LLC appears linked to something called Lakewood Six Solar LLC in New York City. No information could be found about Central Plaza. Lessons LearnedA few take-aways from this second tranche:

We said after the first tranche data was released that it appeared that the program was off to a good start and the results for this second tranche appear to confirm that assessment. Now we need to see the success rate of these projects actually being developed. |

Case Study: Westridge Project One Year LaterWe thought it would be useful to take a look back at a major project one year later and get the client's perspective. For this article we hired free-lance writer extraordinaire Sara Cardine to go back and talk with the folks at Westridge about how going solar has worked out for them. Here is part one of Sara's report (with links to parts two and three at the end.) For the past 100 years, Pasadena's Westridge School for Girls has prided itself on providing a top-notch education that grooms young women into the leaders of tomorrow. As part of a legacy of bringing cutting-edge ideas and innovation to campus and making it all come alive in the classrooms, school officials have made it a goal to pursue and complete at least one project related to sustainability on campus each year. In late 2011, looking forward to the next year, they decided to address a perennial request made by parents and students over the years: that an air-conditioning system be installed in the school gymnasium to keep crowds cool on hot days. While the school could likely raise funds from the parent community to purchase and install a system, the financial and environmental impact of running it and creating a new drain on the power supply were less than sustainable, says Brian Williams, Westridge's Director of Facilities. So, to offset the cost and energy consumption of the desired air-conditioning unit, officials decided to fundraise for another project at the same time, one that would mitigate the cost and consumption of the A/C. They asked parents and students if they'd be willing to raise money to install a solar system on school grounds. Big Plan on CampusSolar energy was not exactly new to the school. In 2009, Westridge had installed a small system on its newly built LEED-Certified Platinum science and math building. There some of the panels were placed near the ground, where students could see them up close and interact with the technology. For the new project, however, school officials were thinking much bigger. They wanted to maximize energy savings by installing a large-scale system that would provide a solid and swift return on their investment and take advantage of a local rebate being offered by Pasadena Water and Power (PWP) that was set to decrease drastically after the end of the year. Ideally, the new installation would generate enough energy to cover the usage from the A/C in the gym and still supply additional power to other buildings on the campus, saving on the school's overall monthly electric bill. At the outset, there were no specific parameters for the project, Williams said, just a location.

With an area of approximately 4,000 square feet, it received direct sunlight throughout most of the day and was elevated enough to tidily keep the operation out of sight. Doing their BiddingWilliams turned to three different solar companies, seeking estimates to help define the scope of the project and determine a total cost that would guide the school's fundraising efforts. The first two companies Williams considered were those the school had worked with on past projects. One was a large, international solar provider that had worked on the 2009 science building installation. The other had previously worked with Westridge on nearby residential properties. Run on Sun, the third provider approached regarding the installation, was the only one the school had not personally worked with before. The Pasadena-based company had contacted school officials earlier that year and delivered a presentation on its installation process, qualifications and services provided. That presentation was fairly comprehensive, and made enough of an impact for Westridge to include Run on Sun in the bidding process. "We didn't have any actual experience with them, but they had very good references that we checked as we went through the bidding process," Williams explains. Finding the right contractor for the job was a thorough search that employed analysis and research. But beyond that, Williams, who's worked in the facilities department for more than two decades, relied on his own gut instinct and experience to determine which company could best get the project done in a short amount of time and leave no detail unchecked. Since Westridge is a privately funded nonprofit, it is not under the same obligation as public entities to accept the lowest contractor bid. Cost, however, was still a primary consideration in selecting an installer. "I have a fiduciary responsibility in my job to make sure the projects we do here are cost-effective and help maintain our campus in a positive way," Williams says. "I can't do anything that doesn't make fiscal sense." The cost estimates provided by the three companies for an approximately 50 kW system were not that disparate from one another, coming in at about $4.25 per watt. One thing Westridge did have to be cautious about in its review of the estimates, however, was the possibility of a provider initially underbidding the project with the intention of requesting additional funds through change orders after a contract had been signed. The contractor who was truly right for the job would be one who provided an accurate estimate up front and diligently held true to that figure. When considering the PWP rebate, Williams knew the school stood to save about half the total cost of the installation over the course of five years. Additionally, all three bidders told Westridge officials they could expect to see a full return on their investment in about seven years. Overall, the project made great financial sense. Since the cost estimates that came in from the three bidders were relatively similar, Williams also analyzed each company's references, experience and credentials. For example, he did consider installers certified by the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners (NABCEP) to have an advantage over uncertified companies. Another important factor was the presence of a licensed electrician on the staff. "It's an electrical installation, and I wouldn't let anybody who wasn't a licensed electrician be on site," he says. "I'm guessing the city wouldn't allow it either." Throughout the selection process, Westridge officials knew they were working under a bit of a time crunch. If they missed the window to apply for the PWP rebate, the project would end up costing significantly more than the amount they had raised. Because of this, hiring an installer who could successfully submit all the paperwork before the fast-approaching deadline, and one they could trust to get the application process 100 percent right the first time, was of critical importance. In this regard, Run on Sun was a standout, Williams says. They promised to take care of all the paperwork, filing within the deadline period and eliminating the extra bureaucratic steps the school would otherwise have had to take. "They managed the whole process - I basically just had to sign the form," he says. The fact that Run on Sun had a strong working relationship with the city of Pasadena was another important consideration that worked in its favor, given Westridge's own solid standing in the community. The attention to detail and professional accountability demonstrated by the company throughout the bidding process brought the local provider to the top of the list, making the ultimate decision to go with Run on Sun an easy one, Williams says. "It was a combination of the cost, return on investment, their relationship with the city, the impression we had with the provider, how they presented the information and their references. We looked at all of it." This Case Study continues with Part Two: Run on Sun Gets it Done! and concludes with Part Three: Advice to the Solar Reluctant. The preceding is an excerpt from Jim Jenal's upcoming book, Commercial Solar: Step-by-Step, due out this summer. |